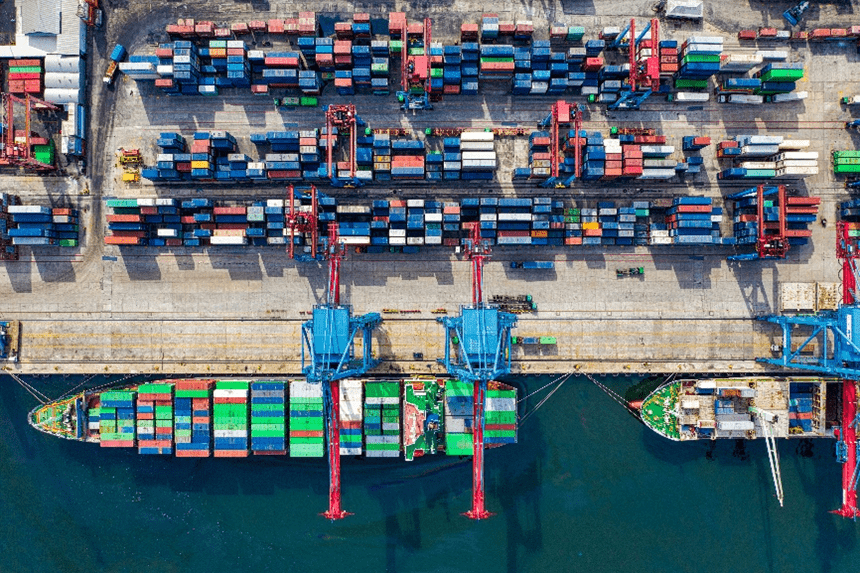

Firms in many industries are currently struggling to adapt their procurement processes. With the supply chain crisis triggered by Covid (and in some parts of the world boosted by Brexit), the procurement of key inputs is slowing, causing production processes to stall and demand to be unsatisfied. As managers suspect that the current crisis may not remain a singular event, insights are needed from management research on how to ensure that operative processes—such as procurement—meet the demands of dynamic competitive environments.

Dynamic capabilities—patterns of recurrent collective activity through which firms adapt to changing environmental circumstances, meet novel challenges, and exploit opportunities—present a remedy to this issue. Firms’ dynamic capabilities manifest in three types of activities: sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring. Sensing comprises firms’ activities directed towards identifying relevant changes and opportunities in their environment. Seizing encompasses activities for developing new ways of responding to observed environmental changes and opportunities. Reconfiguring activities develop and test measures that trigger changes in existing operating processes.

While there exists strong empirical evidence that firms possessing dynamic capabilities can achieve organizational adaptation and performance benefits, scholars still debate how sensing, seizing and reconfiguring activities need to be deployed to achieve these effects. One theoretical position holds that dynamic capabilities need to be deployed in a routine manner, that is frequently and in a highly structured way, while the counter position posits that, particularly in dynamic environments, such routine deployment of dynamic capabilities cannot foster adaptive change. Rather, firms in fast changing environments deploy dynamic capabilities in non-routine, experimental and semi-structured ways. However, we still lack empirical studies that investigate how these seemingly conflicting positions size up. Our recent study published in the Journal of Management Studies provides empirical evidence on two questions central to this debate: Do firms deploy routine dynamic capabilities to achieve change in operating processes? Under which conditions do firms deploy (routine or non-routine) dynamic capabilities?

To answer these research questions, we studied how 103 small and medium-sized firms in Germany deploy dynamic capabilities in the area of procurement. We found—by employing fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis—four different configurations (types) of dynamic capability deployment. Firms operating in high environmental dynamism realized three different configurations of dynamic capabilities. Some firms deployed highly structured dynamic capabilities at high frequency, that is routine dynamic capabilities (Programmed configuration); others deployed semi-structured dynamic capabilities only sparingly (Adaptive configuration); yet others relied on dynamic capabilities that are deployed at high frequency, exploratory and only semi-structured (Experimental configuration). A fourth configuration of dynamic capabilities was deployed in environments of low dynamism (Analytical configuration). Here firms deploy all three dynamic capability activities in a highly structured manner, yet in low frequency.

Contrary to extant research, our findings thus show that environmental dynamism does not seem to determine how routinely firms deploy dynamic capabilities. So, on which other factors does it depend how firms deploy dynamic capabilities? To examine this question, we collected additional data and performed in-depth case analyses of 16 firms deploying each of the found dynamic capability configurations. On this basis, we generated a theoretical framework proposing why and how the interaction of two intra-firm conditions can help us understand when firms deploy a particular configuration of dynamic capabilities under conditions of high, respectively low, environmental dynamism: (1) organizational learning orientation (an entrepreneurial versus a problem-solving mode) and (2) the extensiveness of resource allocations towards dynamic capabilities. Taken together, our study thus uncovered external and international conditions that influence when firms deploy different types of—routine or non-routine—dynamic capabilities.

Our study has implications for both theory and practice. It is among the first to show empirically that the main positions in the theoretical debate on dynamic capability routineness’ both have merit, may be less conflicting than it seems, and thus need not divide the field of study. We find that the routineness of dynamic capabilities (in terms of frequency and structuring) may vary independently and across the three constituent dynamic capability activities of sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring so that firms realize more complex configurations of dynamic capabilities in environments of high and low dynamism than previous research has envisaged. Moreover, our findings contribute to nascent theorizing on internal enablers and constraints that lead to heterogeneity in dynamic capabilities. Our study also has implications for managers who design dynamic capabilities for their firms. For example, managers leading firms in highly dynamic environments should consider how the learning orientation of their organization (entrepreneurial versus a problem-solving) and resource allocation towards dynamic capabilities enable and constrain them in the more or less routine design of dynamic capability activities.

Got interested in reading the full article? Visit the Wiley-JMS website https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/joms.12789

Keywords: dynamic capabilities, procurement, mixed methods

0 Comments