Serendipity – the notion of making surprising and valuable discoveries – plays a major role for individuals and organizations alike. Numerous innovations and inventions such as potato washing machines, Velcro, and Viagra can be traced back to serendipity, and many individuals and organizations credit it as essential to their success. In a recent Journal of Management Studies paper, I embarked on a systematic review of the relevant work on serendipity to understand what truly defines serendipity, what makes it different from other concepts, and how it can be cultivated. Some insights:

What is serendipity, really? And why does it matter?

The review surfaced three necessary conditions of serendipity: surprise (there’s a somewhat unexpected situation); agency (you must act on this unexpected situation); and value (some sort of value emerges, even if it’s ephemeral). These three elements help differentiate serendipity from “blind luck” (which tends to be surprising and valuable but there’s no agency) and targeted innovation (there’s agency and value but no surprise). This leads to a grounded definition of serendipity as “surprising discovery that results from unplanned moments in which our decisions and actions lead to valuable outcomes”. In a way, it’s “active luck”, which is very different from the “blind luck” that creates lots of societal inequality (e.g., due to the “birth lottery”).

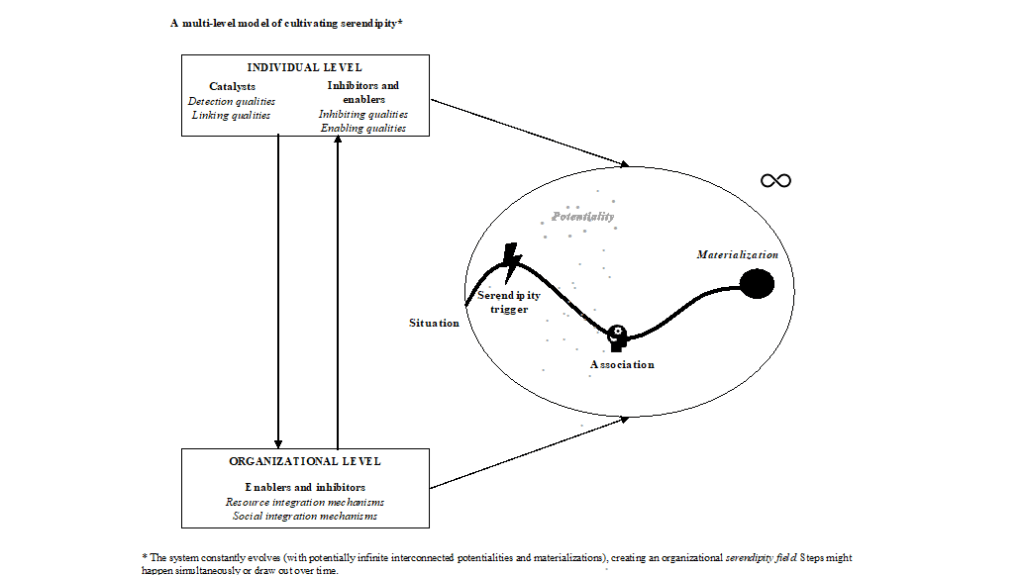

Serendipity is not simply a singular event but it’s a process. There usually is a serendipity trigger (e.g., a random event); someone has to make an association (“connect the dots” to something meaningful); and in an organizational context, it has to be materialized. The example of the potato washing machine illustrates this dynamic: When farmers unexpectedly reported that their washing machines had broken down due to them washing their potatoes in it (serendipity trigger), employees of a white goods manufacturer realized that this might be a market opportunity for potato washing machines (association). The organization invested into the idea, integrated a dirt filter, and turned it into a new product (materialization). This example shows how potentiality can emerge in an organizational context, and how it can be materialized, turning random observations into beneficial results.

How can individuals influence serendipity?

On the level of individuals, there are factors that catalyze serendipity. Those are “detection qualities” such as alertness, curiosity, and intuition; and “linking qualities” such as sagacity, analogous thinking, improvisation, and creativity. However, individuals often hold themselves back from experiencing more serendipity as they might exhibit “inhibiting qualities” such as self-censoring. Imagine having a great unexpected idea in a meeting – but not bringing it up because you don’t feel “ready” or the idea is not “perfect” enough. On the flipside, “enabling qualities” such as cognitive flexibility, perseverance, and social skill can enable serendipity.

How can organizations create the conditions for serendipity?

Organizations can create the conditions for serendipity in two major ways. First, they can improve “resource integration mechanisms” such as the direct resourcing of unexpectedly emerging ideas, and effective evaluation mechanisms (e.g., how do we know that an unexpected idea is worth investing into; investment committees etc. are options). And second, via “social integration mechanisms” such as integrative social networks, effective problem formulation (not over-defining problems), and increasing psychological safety.

Let’s return to the potato washing machine to illustrate these dynamics: an unexpected event (farmers washing their potatoes in washing machines) was observed by alert sales representatives (detection qualities), who instead of discarding the information sagaciously connected the dots, realizing that integrating a dirt filter might make a potato washing machine a viable product option (linking qualities). The company helped materialize this into a new product category by investing into the unexpectedly emerging idea (resource integration mechanisms). The figure below captures these dynamics.

A possible counter-factual (“what could have happened instead?”) could have been the individual not detecting the anomaly; inhibiting qualities such as self-censoring getting in the way of realizing its value; or the company failing to invest due to resource constraints or power dynamics (and thus not materializing the potentiality). In that case, serendipity would have been missed even if it could theoretically have been possible.

What does this mean for individuals and organizations?

These insights have important implications for individuals and organizations. First, they suggest that social actors have agency when it comes to creating serendipity: like training ‘hard skills’ related to finance or engineering, it is possible to train serendipity-related skills such as alertness. My hope is that by providing a ‘vocabulary’ and framework related to the emergence and cultivation of serendipity, it becomes actionable for individuals and organizations alike, allowing executives to no longer pretend that they knew (or planned) everything. Instead of a threat to authority and an ‘error factor’ to be reduced, the unexpected then potentially becomes a source of opportunity and delight.

Second, they suggest that companies can influence their propensity for serendipity by developing organizational enablers (e.g., related to specific social integration mechanisms such as facilitating psychological safety) that incentivize employees to create unexpected positive outcomes for their organization. Serendipity can play a particularly important role in established companies after a leadership transition, in times of radical contextual change, when new opportunities need to be identified effectively, and when new leaders look for new impulses and thus aim to break out of potential path dependencies.

Third, support organizations such as incubators and government agencies can use this multi-level framework to develop support structures that help cultivate serendipity. An appreciation of (the unexpected emergence of) valid local solutions – and investing into those – can help avoid making fixed assumptions about ‘what is best’ for the respective member(s), and help combine a traditional foresight/planning approach with an openness to local knowledge, especially in high-uncertainty contexts. This might lead to important changes in how these support organizations define success: Instead of focusing on how many entrepreneurs graduate an incubator program, for example, celebrating effective pivots might be more effective. This could help social actors explore potentiality even if they already committed to a particular materialization opportunity, and thus, become who they are truly capable of becoming.

Long story short: Serendipity is all about potentiality, and it is upon us and our organizations to “see” (and/or sow) this potentiality – and to materialize it in ways that align with their core values and priorities.

0 Comments