The “theory always” imperative in management

Contemplating the role of theory in management has always been a playing field for the big names of the discipline: Bacharch, Weick, Hambrick, Gioia, Sutton, Suddaby, Langley, or Eisenhardt. No scientist would deny that theory is important. But hardly any other discipline seems quite as obsessed with “theoretical contributions” as management.

There are competing theories about why that is:

The relevance theory says that after an initial period when management education was nothing more than practical advice, skills and tools, theory became so heavy in order to show that management research had things to offer that went beyond honing managerial behaviour.

The science theory says that management suffers from physics envy or other inferiority complexes and insists so much on theory for it to be seen as a scientific field on par with the natural sciences—while interestingly economics has become heavy in mathematics and moved “beyond theory”, supposedly for the same reasons.

A heated debate, which misses the main point

No matter where the dominance of theory comes from, over time, more and more scholars have come to claim we have been overdoing theory and that this has caused serious limitations. For example, it has inhibited the discipline’s ability to deal with current societal challenges.

The vocabulary, which scholars have used to express their unease about the situation, was never shy. Jeff Pfeffer has called for draining the “management theory morass” and Dennis Tourish went as far as equating all of management theory with the production of nonsense.

While the discussion about theorizing in management seemed to have slowed down over the past decade, it picked up speed in the last two to three years, especially since Tourish’s pertinent provocation.

Some colleagues have urged us to “fuck science” and to re-humanize management, challenging theory’s objectification, while others have questioned the need of growing “theoretical balls” to be allowed to theorize in management, challenging the dominance of the debate by masculinity. Some have proposed alternative, non-explanatory types of theory and thus greater theoretical diversity, while others have contemplated how to produce “impactful theories”, bringing the long-standing empirical debate about “what’s interesting vs. what’s relevant?” into the realm of theory.

While these new propositions shall prove important as to the types of theory we will have available, they have little bearing on the question of: why theory at all?

And more specifically: When do we (not) need theory? And how can management scholars theorize so that they contribute to progress in a field rather than undermine it?

Increasing reflexivity about what theory does

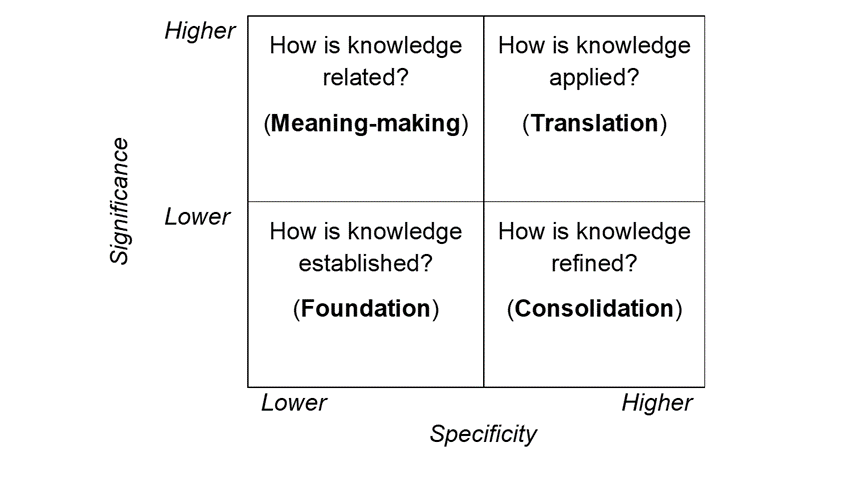

In Calibrating for progress, published in the Journal of Management Studies, I argue, to answer these questions we need to better understand the different instrumental functions of theory. Theory can be mainly concerned with: (1) building a new foundation for knowledge, (2) consolidating knowledge, (3) making meaning between strands of knowledge, or (4) translating knowledge.

It is hard to serve any single one of these functions well, let alone several at the same time. I show that in management, researchers have a tendency of doing too much of everything, for instance in order to comply with the scholarly myth that you have to make three theoretical contributions. My hope is that, once scholars better understand what theory does, in which context and under which conditions, they may not only become more prudent (or daring) in their theorizing, but also recognize where and when we need no new theory at all—and instead more empirical analysis, or methodological detail or reflection.

I further show how this should particularly be the case when empirical findings are very important yet not theoretically intriguing (confined), very relevant, original and new but hard to grasp (phenomenon-stage), or extremely vast and all encompassing (doubly-loaded), so that theorizing becomes very hard or unreasonable.

To be clear: We should have any of these types or research. In fact, we should have much more of them. Precisely because of this, it should not matter that either (a) they are limited in their power of generating new theory or that (b) we should refrain from theorizing within them because the resulting theories would be mere speculation.

Now, what does this mean for management’s way forward?

Small adaptations will not do the job

In addition to outlining the practical uses of my framework for authors, reviewers and editors as they write or assess new research, I consider what needs to change in how management deals with theory.

I disagree with existing, rather incremental pitches of what to do to address our problems, such as favouring abductive theorizing over other types of theory, explaining better what we do when we theorize, or tuning down unit theory (more fine-grained and incremental) in favour of programmatic theory (more encompassing). While these suggestions have their benefits, they do not really address the core problem: that we have too much theory which helps us understand too little of the world that surrounds us.

Instead, I suggest we cut down on hybrid articles that combine empirics and theory in favour of more room exclusively dedicated to theorizing as well as more space for “no theory”-research. Only this way can we amplify the quality of theory building and leverage the discipline’s empirical richness at the same time. Only this will enable us to calibrate for more progress.

0 Comments