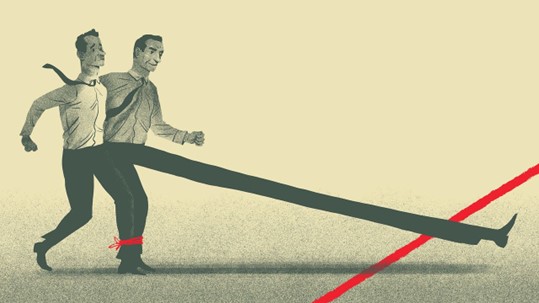

What happens when a change initiative succeeds—but its creators are pushed aside? This research explores how change recipients can hijack a transformation—adopting its goals while sidelining its initiators. Based on an ethnographic study, we introduce cooptive rejection, revealing how change can succeed even as its agents are discredited. The result: a sharp rethink of what success looks like in organizational change.

Why do some organizational change projects succeed even when those who champion them fall out of favor? In our recent study published in the Journal of Management Studies, “How Change Recipients Become Rivals: Legitimacy Dynamics and ‘Cooptive Rejection’ in Organizational Change”, we explore this puzzling paradox and introduce the concept of cooptive rejection—a process by which organizational members embrace a change initiative while simultaneously sidelining its initiators.

This idea emerged from a deep, three-and-a-half-year ethnographic study of a major transformation in Region Alpha, a large French public organization. There, we observed an unusual trajectory: although the organization ultimately adopted many of the changes promoted by a newly formed internal change agency unit-called “Transformation Department” (TD)- that very unit—and its leaders—were progressively undermined and rejected, leading to its disappearance.

Challenging a Core Assumption in Change Management

Much of the literature in change management and legitimacy theory assumes a tight link between the legitimacy of a change agent and the legitimacy of the change they promote. Logically, if you don’t trust the messenger, you reject the message. Our study complicates this view.

In Region Alpha, the TD was created to implement fancy new ways of working—telework, flex-office, managerial agility—encouraging more autonomy, flexibility, and innovation in the workplace. Its leaders pushed hard for change. But despite their efforts, they never earned the trust of key civil servants. On the contrary, they were often seen as outsiders promoting private-sector fads unsuited to the public service. And yet, the changes they championed were progressively adopted and even celebrated.

In other words, our study challenges the common belief that a change agent’s legitimacy is a prerequisite for successful transformation.

Cooptive Rejection: When Recipients Take Control

How can a change project succeed while its champions are sidelined? We call this dynamic cooptive rejection—a subtle but powerful process in which organizational members adopt and advance a change initiative while simultaneously discrediting and excluding its original promoters. This occurs through three intertwined mechanisms.

- First, change agents seek legitimacy by promoting bold narratives and positioning themselves as transformation leaders. But these self-promotional strategies can backfire—provoking resistance when they clash with organizational norms or appear self-serving.

- Second, recipients appropriate the change, selectively adopting tools, language, and practices that serve their needs. They reframe the initiative in ways that align with their values and local contexts, effectively taking ownership and embedding it on their own terms.

- Third, recipients discredit and substitute the change agents. As they gain confidence, internal leaders undermine the original team—questioning their credibility and sidelining them from key decisions. Over time, the very people who adopt and implement the change also rewrite its origin story, omitting or downplaying the role of its initiators.

In sum, the change spreads—but its creators are pushed aside.

Why It Matters

This dissociation between project and promoter has major implications. First, it shifts our understanding of power and influence in change processes. Recipients are not passive—they can actively reshape, reframe, and redirect change initiatives. Sometimes, they do so more effectively than the original change agents.

Second, it shows that legitimacy is not a singular judgment. It is multifaceted (instrumental, moral, relational), audience-specific, and fluid over time. In our case, while the TD never gained legitimacy on the moral ground, the change they promoted was eventually seen as useful (instrumentally legitimate) and even aligned with the values of the public service—once it was reframed by insiders.

Finally, it highlights the political nature of organizational change. Internal actors can engage in legitimacy rivalry—a subtle power play where control over the narrative becomes as important as control over the tools.

Takeaways for Managing Organizational Transformation

- Legitimacy is not transferrable. A change project can succeed even if its promoter is distrusted. Conversely, a trusted change agent might see their initiative fail if it doesn’t resonate. Leaders should not assume that “being right” or “being credible” guarantees support.

- Anticipate appropriation. Change agents should be aware that others may adopt—and adapt—their projects. This isn’t necessarily failure. In fact, it may be a sign of success. But it requires letting go of control and focusing on outcomes rather than recognition.

- Mind the moral tone. When change is framed in ways that seem to challenge identity, status, or values, resistance is likely—even if the substance is sound. The TD’s early framing as a radical “cultural revolution” triggered backlash. Later, the same ideas gained traction when reinterpreted as pragmatic tools for everyday work.

- Watch for cooptive rejection. Organizations should pay attention when enthusiasm for change is high but support for the change team is dwindling. This could signal a need to recalibrate roles, renegotiate sponsorship, or even step aside to let the change embed.

Although our case focuses on internal change agents, these takeaways resonate strongly with the experiences of external consultants—whose involvement can, paradoxically, become a liability for the change they promote. They may introduce valuable transformation ideas, but the very fact that these are carried by external actors can provoke suspicion or resistance, especially when perceived as disconnected from the organization’s culture or values. Clients often appropriate and adapt the initiative to fit their own context, gradually sidelining the consultants and recasting the change as internally driven. In this sense, consultants may achieve lasting impact precisely when they relinquish ownership and visibility.

Final Thoughts

Our study raises a deceptively simple question: Did the change agent succeed in their mission? On one hand, the transformation took root. New ways of working spread. The organization evolved. On the other hand, the very people who championed the change were sidelined, discredited, and ultimately erased from its story.

This tension invites a deeper reflection. Perhaps real success doesn’t lie in staying in control, but in catalyzing a shift that others appropriate and make their own. Maybe the most effective change agents are those willing to let go—even to be sacrificed—so the change can live on.

To lead change, then, is to risk becoming dispensable. And sometimes, the final measure of success is not recognition, but disappearance.

0 Comments