Shaleen Gopal, K S Manikandan, J Ramachandran

What is the puzzle?

There is a broad consensus that unrelated diversification is value destructive in developed economies and profitable in economies with poorly developed institutions. However, the picture is less clear in emerging economies. While some researchers expect pro-market reforms to render unrelated diversification unviable (as in developed economies), others have pointed to the continued relevance of conglomerates in emerging economies[1]. We attribute this gap in our understanding to the failure to distinguish firm-level and business group-level strategies in emerging economies.

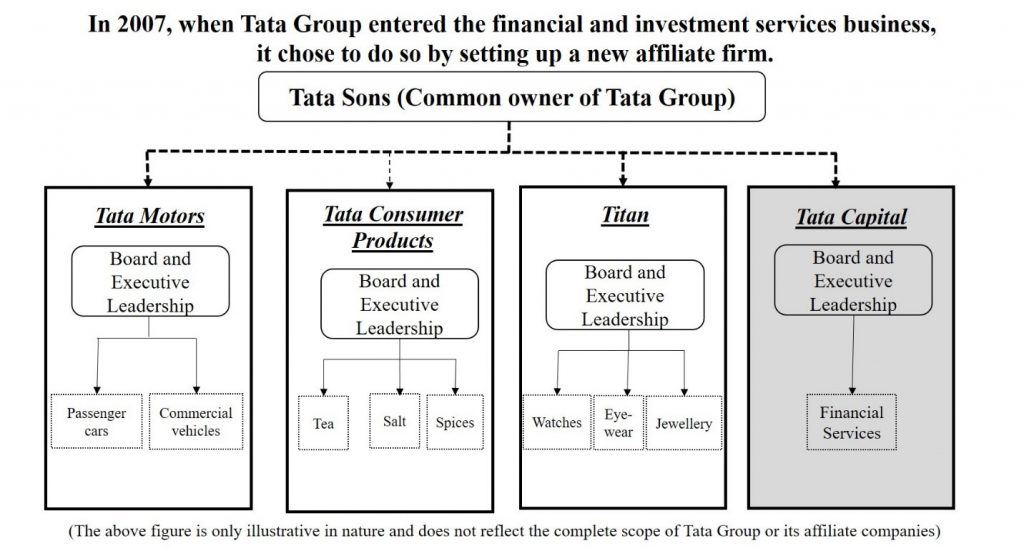

Business groups refer to a set of legally independent firms operating in diverse businesses with a common controlling owner. For example, in India, Tata Group comprises 28 listed companies operating in diverse businesses ranging from software to hotels; the holding company Tata Sons is the common owner. Business groups diversify interchangeably at two levels—by expanding the unrelated scope of existing affiliate firms (affiliate firm-level) as well as by housing new unrelated businesses in new affiliate firms (business group-level) (see Figure 1). Thus, we investigate firm-level and business group-level diversification separately on a sample of Indian firms (1819) and business groups (269) in India over a fifteen-year period following the initiation of reforms (1993-2007).

Figure -1: Business group diversification

Firms reduced scope but business groups expanded scope following reforms!

Our findings confirm that in emerging economies too, liberalized product markets and increased shareholder power limit firm scope. As theorized, all firms—including business group affiliates—reduced their unrelated scope following pro-market reforms, to enhance competitiveness and improve value.

However, pro-market reforms did not curb expansion of business groups. In the pre-reforms period, the common owners of business groups diversified interchangeably at both firm- and business group-levels. Pro-market reforms render the unrelated diversification of the first variety—increasing unrelated scope of existing affiliate firms—unviable. However, the underlying drivers of diversification—creating value and diversifying (unsystematic) risk—remain unchanged. We theorize that business group common owners will use their entrepreneurial abilities, exploit their vantage point in the group and the opportunities afforded by pro-market reforms to enter new businesses to create value and diversify risk. However, following the preference for focused firms in the changed institutional context, they will house these new businesses in new affiliate firms, thus resulting in an increase in both the number of unrelated businesses and the number of affiliates at the level of the business group. Our findings confirm these expectations.

Taken together, our findings on the differential diversification behavior at the firm- and business group-levels support our thesis that the logics undergirding them are fundamentally different. The former is driven by the pressure to create value by improving competitiveness and performance. The latter (business group-level diversification behavior) is driven by the motivations of the controlling shareholders to exploit their vantage points of ownership and control to create value and diversify their (unsystematic) risk.

As market institutions strengthen, managers of public companies focus on building a portfolio of related businesses while owners pursue new unrelated opportunities.

Our findings resonate with the speculation that as institutions develop the locus of unrelated diversification may shift away from managers of public corporations with widely dispersed shareholding to different types of ownership structures that are characterized by significant ownership[2]. It has been seen that in developed economies, while strengthened institutions have discouraged unrelated diversification, conglomerates have not disappeared; they “have merely become private equity companies, and as such they appear to be flourishing”[3]. While the shift in the locus of unrelated diversification in developed economies is driven by the mitigation of misalignment of interests between shareholders and managers, strengthened capital market institutions in emerging economies address the imbalance between shareholders, viz. the principal-principal problem[4]. The locus of unrelated diversification remains vested in common owners of business groups as in the past, but strengthened institutions circumscribed their ability to diversify interchangeably, leading them to execute their unrelated diversification strategies differently.

We believe that the emphasis on the organizational form of business groups has hidden the novelty of the ownership structure and its ability to create value and diversify (unsystematic) risk by adapting its model of governance to the changes in the institutional context, in plain sight. The strategy of business group common owners aligns with the prescriptions of both corporate diversification scholars—that discourages firm unrelated diversification—and corporate finance researchers—who encourage unrelated diversification by shareholders.

Unrelated diversification has not disappeared. It is managed differently.

The conventional prescription with respect to managing diversification is to either divest (and focus) or divisionalize (organize businesses as M-form). Divesting implies letting go off profitable opportunities for want of a better way to manage portfolio diversity. On the other hand, M-form also has limitations[5]. It prevents the simultaneous pursuit of cooperation and competition between divisions required to harness synergies for related businesses and governance economies (i.e., efficient allocation of resources) for unrelated businesses, respectively. Our findings offer business groups as an effective alternative to govern large-scale diversification. In fact, business groups closely resemble private equity firms who are also characterized by the presence of a significant owner who influences strategic choices across a set of legally independent firms in diverse businesses. In these alternative forms, the executive leadership of affiliate firms (or investee companies in the case of private firm) principally focus on gaining scope economies by fostering cooperation among business units in their portfolio of related businesses. The task of harnessing governance economies is undertaken by influential owners (common owners in business group or partners in private equity firms).

The full article is available at the website of Journal of Management Studies and can be accessed here – https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/joms.12680

REFERENCES

[1] Ramachandran, J., Manikandan, K.S. and Pant, A. (2013). Why conglomerates thrive (outside the US). Harvard Business Review, 91, 111-119.

[2] Schommer, M., Richter, A., & Karna, A. (2019). Does the diversification–firm performance relationship change over time? A meta‐analytical review. Journal of Management Studies, 56, 270-298.

[3] Zenger, T. (2013). Strategy: The uniqueness challenge. Harvard Business Review, 91, 52-58.

[4] Young, M. N., Peng, M. W., Ahlstrom, D., Bruton, G. D. and Jiang, Y. (2008). Corporate governance in emerging economies: A review of the principal–principal perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 45, 196-220.

[5] Ramachandran et al. (2013)

Hi, Thank you very much for the article.

Can you share some examples of the business houses who has not diverisified (unrelated) and has become less significant or less visibile or not able to survive?