Dynasty and innovation: A tale with two sides

An intriguing aspect of many family businesses concerns their dynastic outlook. Popular television series like Dynasty and Succession capture the imagination of many viewers, and the business press often puts the spotlight on long-standing dynastic family firms, such as the 1,000-year old Japanese firm Ichiwa which recently featured in a New York Times piece. Yet, among scholars, one critical question has been surrounded by controversy: are business-families that have dynastic ambitions – and thus intend to transfer the firm to the next family generation – more or less inclined to pursue risky growth opportunities by making substantial investments in innovation? In other words, does dynasty boost or bust innovation?

Several academics have suggested that dynastic ambitions are good for innovation investments because such transgenerational aspirations significantly lengthen the business owners’ time horizon, which should favour investments in long-term growth. Others have emphasized that the intention to pass the family business on to the next generation makes business owners much more conservative with a strong focus on preservation and risk avoidance, thereby discouraging investments in innovation. Hence, the literature lacks coherence on this topic.

This boost-or-bust question is not without consequence for the practitioner and policy field. As a growth-minded investor, the presence of dynastic ambitions might steer you toward or away from family firms as portfolio companies. Zooming out, in most economies more than half of all firms are family-owned, and (in our sample) about half of these family firms can be characterized as having dynastic ambitions. This means that, in aggregate, the innovation spending choices that these firms make have strong implications for the innovation potential of entire economies and, accordingly, policy-makers may seek to influence the presence of dynastic ambitions among business-families. But in what direction? To answer that question, we need to resolve the dynasty-innovation puzzle.

Gambling toward reconciliation

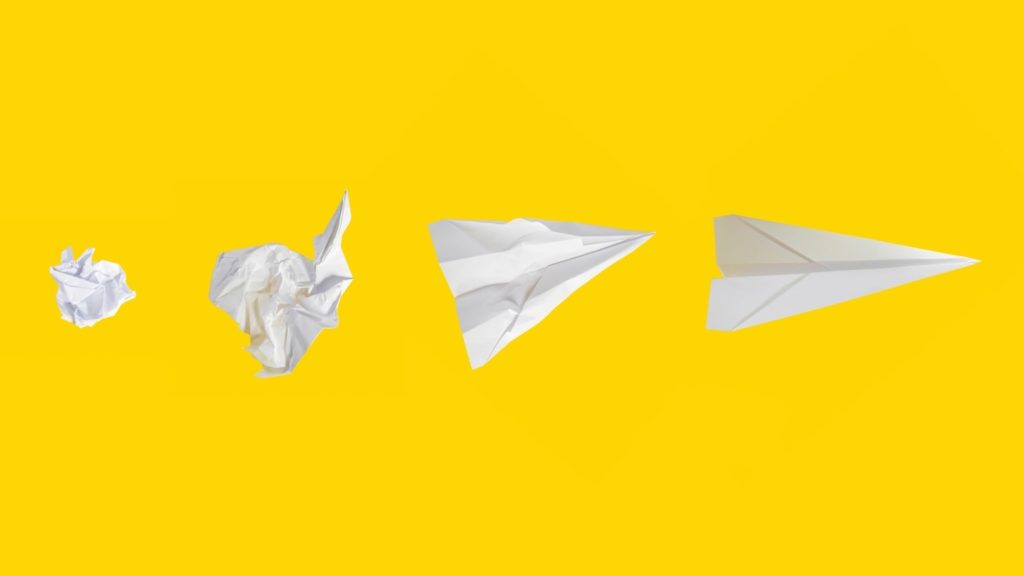

In our study, published in the Journal of Management Studies, we explain that there is truth to both sides of the story. Yes, dynastic ambitions can render business owners more farsighted and more willing to invest in innovation to pass on a more robust and better-positioned company to their offspring. And yes, these very same ambitions may render them more concerned with stability and preservation through risk-avoidance and, thus, result in reduced innovation spending. How so? Well, it depends. Here it helps to frame innovation spending as a “gamble”, as is typically done in prospect theory (which won Daniel Kahneman the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002).

The “gamble” simply refers to the fact that the amount to invest in innovation concerns a risky choice, with potential gains and losses. We know from prospect theory that people attach a bigger weight to losses than to gains, which is referred to as loss aversion. We then go on to explain that dynastic ambitions can have two different effects on the evaluation of such gambles: On the positive side, it lengthens the evaluation period over which prospective returns from innovation spending gambles can be aggregated, which curbs the effect of loss aversion and thus boosts innovation spending. On the negative side, should the play of a “gamble-that-goes-wrong” jeopardize the entire system (in our case, the family business), then having dynastic ambitions would actually lead to a higher experienced loss – namely, the additional loss of the socioemotional value attached to dynasty (i.e., you would not only loose the firm, but also the ability to pass it on to the next family generation as a valued objective).

In other words, the implications for gamble-level choices depend crucially on the system-level hazard position. As long as the system can easily absorb possible gamble losses, this dynastic intent of passing the baton should increase the willingness to play such gambles; yet, as soon as gamble losses may potentially undermine the viability of the system as a whole, for instance because the system is close to resource exhaustion, this intent should significantly lower the gamble’s attractiveness. This reveals that a key contingency variable will be the bankruptcy risk of the firm. The further away from bankruptcy (i.e., the higher the firm’s credit rating), the more dynasty will boost innovation investments; and the closer to bankruptcy (i.e., the lower its credit rating), the more dynasty will bust innovation investments.

We tested our ideas on a sample of around 3,900 German companies, and the empirical findings support our ideas. Indeed, we find that as a firm’s credit rating goes from high to low, the effect of dynastic ambitions on the level of innovation investments goes from significantly positive to significantly negative. The average effect of dynasty turns out to be positive, with family firms having dynastic ambitions on average spending about 70,000 euro per year more on product innovations than family firms without a dynastic outlook. Interestingly, we also find that family firms with dynastic ambitions and a sufficiently high credit rating even invest more in innovation than similar nonfamily firms, which challenges and qualifies the conventional wisdom that family firms underinvest in risky growth opportunities relative to their nonfamily counterparts.

Secondary policy effects

Our study refers to implications for employees, investors, and policy-makers. Here, we focus on the latter. Through policy instruments like gift and inheritance taxes, policy-makers can influence the prevalence of dynastic intentions among business-families. Yet, beneficial tax regimes are often criticized in debates about economic inequality and intergenerational justice. In Germany, for instance, related concerns played a role in a recent reform of the inheritance tax law code, which was a reaction to a ruling by the German Federal Constitutional Court which declared that previous tax benefits were too generous. Our results inform this societal debate by revealing possible secondary effects of gift and inheritance tax regulations; to the extent that they affect the prevalence of dynastic ambitions within the population of family-owned firms, tax regulations related to intrafamily transfers of family firm assets and shares will have implications for these firms’ investments in innovation. Such secondary effects should be taken into account by policy-makers concerned with supporting innovation in the private enterprise sector.

Full article can be accessed here: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/joms.12787

Keywords: family business, dynasty, innovation management, creditworthiness.

0 Comments