Chance favours the prepared mind only. – Louis Pasteur

Why would a team or project incentivised to do X change their ways to do Y? More broadly, how and why would a firm change towards a goal that has no direct incentive to pursue? We asked these questions in a recent study published in Journal of Management Studies conducting over 40 interviews studying a group of researchers from MIT and Nova Lisboa who drastically changed their strategic trajectory despite having no incentives to do so. They moved from doing research with the aim to publication in order to advance their individual careers, to founding a social venture ‘Patient Innovation’ which they have no professional incentives to engage with but instead takes away time from the activities on which they are evaluated on for career advancement (e.g., publications, teaching, funding).

Today, Patient Innovation is a multilingual platform that encourages people from all over the world to post, share, discuss and evaluate solutions, advice and adaptations for improving the lives of people affected by rare diseases with over two million visitors yearly. Numerous distinguished individuals support the platform, including Nobel laureates and renowned scientists across the world, who serve on the platform’s Advisory Board. The medical conditions vary from genetic disorders, such as Angelman syndrome malaria, and Alzheimer’s disease. Healthcare is a grand challenge and affordable healthcare is still a big problem today. Although on average, people live healthier lives today, many still die from preventable diseases. One culprit is the demand-driven focus of the pharmaceutical industry, which makes costly investments in high-margin treatments for ‘rich men’s’ problems while neglecting commercially unattractive rare and ‘poor men’s’ diseases (e.g., malaria). The 2020 pandemic exposed the fragility of our healthcare systems and the innovations we prioritise, as even cutting-edge innovations could do little to stop the coronavirus.

However, the question remains, why make a change towards a goal one has no immediate incentives to do so? Drawing on this case of Patient Innovation, we illustrate how they changed their purpose from core goal of producing scientific publications for professional career advancement instead created a social platform that provides global access to affordable ‘homemade’ user-driven solutions to rare diseases. As creating social impact became the organisation’s core mission, it put academic research on the backburner despite pressure to publish. We illustrate now three pieces of advice which helped the group to shift their attention and radically change their activities:

How to embrace change? – 3 Takeaways

Our analysis revealed that (1) embrace serendipitous inspiration, (2) follow your moral emotions (What is the ‘right’ thing to do?), and (3) the power of socially conscious users and catalysts, induced by their surprising and rousing findings led the academic team to reframe its core purpose.

Takeaway 1: Embrace Serendipitous inspiration.

In 2011, the group surveyed over 500 patients with rare diseases and their caregivers to explore what drives patients to develop and share solutions. Notably, 40 participants in the study, or 8% of the sample, reported engaging with innovations that were evaluated as novel by two medical professionals. These results were ‘surprising’ and ‘pivotal’ for what followed. The surprising discovery that 8% of people had created novel medical solutions but did not share them shifted the team’s attention away from pure academic research, towards seeing their findings as ‘inspirational’ and from a different ‘light of day’ (Interview 11). Serendipity refers to ‘search, with unintended discovery’ (Dew, 2009, p. 735), and is ‘distinct capability, namely that of recombining any number of observations… that appear to be meaningfully related’ (Liu and De Rond, 2016, p. 434). It requires prior experience, previous skills, a ‘prepared mind’ and purposeful action, but also favourable accidents that facilitate discoveries. Serendipitous inspiration played a central role as in enabling change, helping actors to recognise the discovery’s potential and ensuring that it could benefit more people in need. Hence, without the recognition that the ‘8%’ represents something novel and worth pursuing, Patient Innovation would not exist today, and the research findings would likely be confined to academic journals with limited readership, rather than benefiting the community at large.

Serendipitous inspiration was necessary for recognising alternatives and options, and to trigger innovative behaviours that deviate from established paths. However, while serendipitous inspirations are part and parcel of innovation, they may not necessarily motivate actors to change, and transcend self-serving interests and devote themselves to responsibly serving a collective cause in the absence of moral emotions.

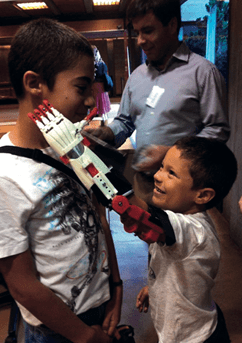

Takeaway 2: Follow your moral emotions (What is the ‘right’ thing to do?). The second key advice is following your moral emotions, which amplify the potential impact of the project, necessary for team members to transcend self-interest and pursue a collective cause. Team members described how empathy for those affected and their families, including personal encounters, and the aspiration to share solutions with the wider community were pivotal in the decision to move away from a research focus. Take, for example, the mother of a boy without hands coming to the university and asking them to print hands for her child. Direct and at times immersive engagement with affected people and their personal stories led group members to move away from their focus on ‘seeing them as numbers and pursuing statistical analysis’ (Interview 35) from a strictly theoretical point of view towards relating to them at a more personal level as fellow humans. These experiences led them to increasingly question their purpose and to develop a sense of moral obligation to consider the wellbeing of their research subjects.

Moral emotions are ‘emotions that are linked to the interests or welfare either of a society as a whole or at least of a person other than the judge or agent’ (Haidt, 2003, p. 853) concerning what is right and wrong or good and bad. They are ‘feelings of approval and disapproval based on moral intuitions and principles… the satisfactions we feel when we do and feel the right (or wrong) thing, such as compassion for the unfortunate or indignation over injustice’ (Jasper, 2011, p. 287).Accordingly, what actors perceived as ‘hard to ignore’ created strong moral considerations to engage in an ‘adventure which we usually wouldn’t embark on’ (Interview 12). Our analysis indicates how actors were intrigued by compassion, empathy and feelings of ‘what is right to do?’. Moral emotions direct the innovation behaviour towards addressing a collective cause with a sense of responsibility (e.g., ensuring proper vetting and governance of solutions), instead of engaging in self-serving activities geared towards career advancement or self-promotion.

Takeaway 3: Make use of the power of socially conscious users and catalysts. A third key recommendation from this study illustrates the crucial role was the support of socially conscious users and catalysts in order to scale. A group of motivated users who had devised creative solutions ‘at home’ further amplified the significance of their research findings (e.g., the Robohand – see picture, and solving the aortic root problem by treating it as a ‘plumbing issue’). The support of influential individuals, such as Nobel Laureate scientists, was also a powerful driver. This effect was further amplified, in which they turned a failed experiment into a sharing platform designed entirely to create a positive societal impact. These catalysts facilitated scaling up the platform and their public endorsements led to its global recognition which led within few months of 500 medical solutions to be uploaded on the platform. The sheer number of patients and caregivers, the enormity of their homemade solutions, and their overwhelming engagement in sharing their solutions fuelled their conviction to prioritise the non-profit platform.

With this power of the community, actors could not ‘simply go back to run regressions’ or ‘write another paper for a conference’, even though their commitment to a societal cause diverted the research group away from their initial goals.

Overall take away

Not all change requires these aspects or serendipity. Also, managers may be reluctant to admit serendipity, preferring to credit their deliberate strategies and planning rather than ‘luck’. Nonetheless, serendipitous inspiration is common in innovation, as in the discovery of Post-it Notes, and in medicine development. For instance, Pfizer’s sildenafil citrate was meant to address hypertension but became the key ingredient in its blockbuster drug, Viagra. Yet, serendipitous innovations may not necessarily turn out to be responsible in terms of their impact on target audiences, and this aspect demands further attention. However, an important question for managers and firms remains, to create an environment which fosters and allow for serendipitous discovery, and allow employees room for their ‘pet projects’!

Keywords: grand challenges, healthcare, innovation, rare diseases, impact, academia, responsible innovation

0 Comments