Alex, a middle manager working in the HR department who is right on track to the next promotion, dials into the video call with the executive board. Over the last weeks, unbeknownst to anyone, Alex had pushed some high performing subordinates to “finally stop crying and deliver upon their potential”. Afraid of Alex’ emotional outbursts, the team had put in lots of overtime and improved the project yet again.

The meetings starts. Alex is complemented on the new project numbers. After Zoe, the head of HR, reports about the challenges related to introducing the new hybrid work policies. When she ends her presentation, the usual virtual applause appears, and a few people write into the chat – among others, Alex who notes that “Zoe’s ideas will lead us into a bright future of work”. She must admit that she feels flattered; the last months have been rough.

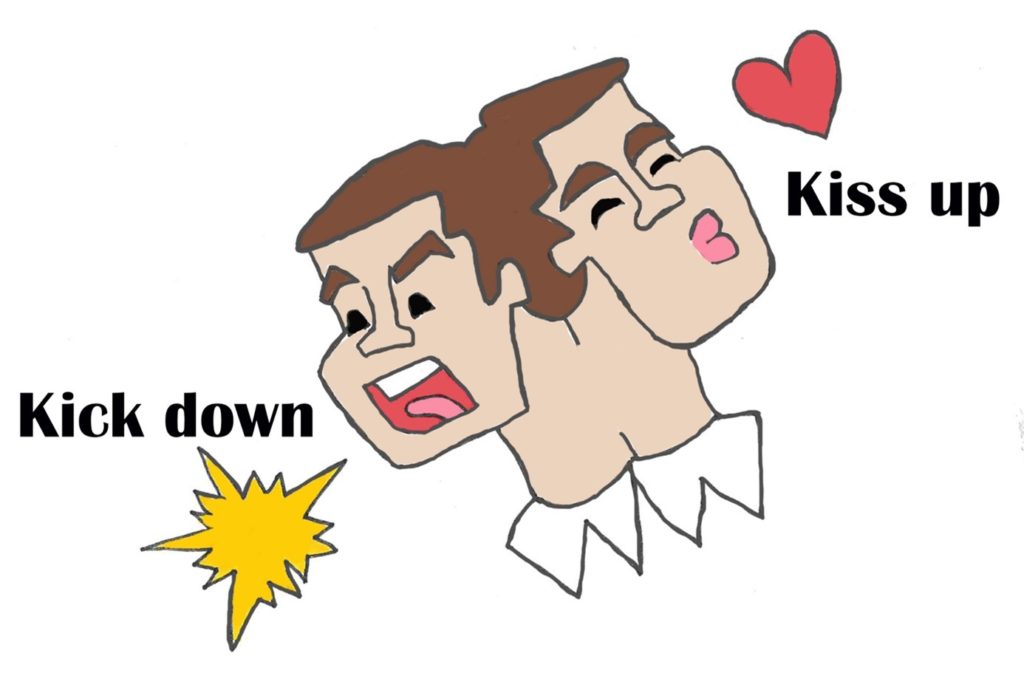

Kiss-Up-Kick-Down in Action

The introductory example illustrates a phenomenon that you have probably experienced yourself or at least heard about before: Middle managers who pressure and intimidate their employees to squeeze out maximum performance – and then take the whole credit to advance their career when brownnosing toward their own bosses. In our recent paper, published in the Journal of Management Studies, we formally define this behavioral combination as the Kiss-Up-Kick-Down (KUKD) phenomenon and offer propositions to better understand how, when, why, and with whom some middle managers may engage in KUKD on the way to their next promotion.

Specifically, we introduce KUKD as a bidirectional dynamic behavioral pattern that (1) involves two behavioral strategies, namely kissing-up and kicking-down, which are (2) directed toward upper and lower hierarchical levels (3) in a dynamic way that is contingent on the resources available to the focal middle manager and the managers around them over time.

KUKD to Gain Resources for Career Advancement

Resources refer to anything that help people or organizations to achieve their goals; as such, they are crucial to understand why middle managers may engage in KUKD on their way to the next promotion. The more resources middle managers accumulate, the more likely they can realize the next career step. This allows them to avoid getting stuck in a highly competitive middle management position, which is sometimes also referred to as the bottleneck of corporate careers. The resource-logic of career advancement also entails that resource-poor middle managers are more prone to use KUKD, particularly if they are close to the next promotion.

Where Resources Come From

From upper hierarchy levels, middle managers can obtain sponsorship resources (i.e., access to informal networks and information, career sponsorship, emotional and work-related social support, training and skill development opportunities). From lower hierarchy levels, middle managers are able to extract productive resources (i.e., labor or work output) from. Notably, by kicking down, middle managers can preserve their own energy (i.e., psychological resources) and use this energy to keep up the exhausting kiss-up behavior toward their superiors.

Who are the Primary Targets of KUKD?

Not all superiors and subordinates may be equally suitable sources of sponsorship and productive resources, respectively.

First, superiors who possess a rich resource pool themselves are less susceptible to a middle manager’s kiss-up behavior than those who are resource-poor. In the situation described in the beginning, Zoe has gone through a tough period and her standing is comparably low; she gratefully accepts the flattery of Alex. In contrast, a resource-rich superior needs less support from others.

Second, the oppositive dynamic unfolds on the lower level: Here, resource-rich subordinates are (at least in the short-term) particularly likely to work hard for their kicking-down middle manager. With no immediate escape at work and an interest in successfully continuing their current career-track, resource-rich subordinates put in high effort in the hopes of alleviating the kicking-down experience. In contrast, subordinates who are low in resources may directly enter an unproductive and emotionally exhausting depletion stage when being kicked.

The Diminishing Returns of KUKD Over Time

The longer middle managers use KUKD, the less effective it becomes. On the one hand, low-resource superiors habituate to kissing-up behaviors and increasingly refill their own resource pool. On the other hand, even initially high-resource subordinates give up over time and become depleted. As a results, middle managers need to engage in even more kiss-up behaviors to still receive sponsorship resources from superiors (i.e., the middle managers’ need for psychological resources increases), while at the same time the middle managers receive increasingly less resources from subordinates through their kick-down behavior. As middle managers then kick down even harder, subordinates may become less accessible because they call in sick or suffer from burnout.

How Can Practitioners Use Our Research?

Based on the model that we developed, we expect that certain organizational environments may either nourish or impede KUKD behaviors. As such, the following four factors might help to identify those organizations (or organizational parts) where KUKD is more or less likely to occur.

First, in organizations where regular promotions are a central part of the career concept, the resulting culture may implicitly pressure managers into KUKD. To be more specific, this might be the case in an “up or out” culture that characterize for example many consultancies in which people must leave the company if they do not get promoted in time.

Second, traditional incentive systems that focus on the “hard numbers” achieved by individual middle managers who are ranked against each other may (unintentionally) increase the attractiveness of KUKD as a go-to strategy for career progress. This is because in such systems, middle managers are competing directly with each other and subordinates’ assessments are rarely considered—because the output is all that matters, kicking-down can easily result in competitive advantages. After all, promotions are one of the most salient artifacts of organizational culture. As such, many people will emulate successful career strategies—and if those are destructive, then there is an increased chance that KUKD will be institutionalized and undermine the meritocratic ideal.

Third, companies with higher power distance, which refers to the degree to which employees feel they cannot bypass or challenge management authority and organizational hierarchies to raise concerns, may offer a more fertile ground for KUKD. In contrast, in companies characterized by lower power distance, it is more likely that a middle manager’s subordinates and superiors will interact and develop a realistic (i.e., disreputable) view of the middle manager’s behavior.

Fourth, and particularly importantly when designing the future of work, in remote or hybrid work settings, middle managers have even more chances to strategically channel communication to specific target groups. At the same time, the very same middle managers also experience a lower risk of informal conversations between their subordinates and superiors that could reveal the KUKD behaviors when the company does not explicitly foster such chats.

So what to do? When organizations do not want to change their structural features or culture, they can still try to reduce KUKD by making superiors more aware of what is being done to them and others in order to circumvent middle managers’ efforts. One easy first step could be to introduce institutionalized and continuous upward feedback systems, which can help to improve middle managers’ behavior. For example, managers at Google are regularly evaluated by their subordinates in an upward feedback survey, and they can only progress their careers when the results indicate that they treat their employees respectfully. Likewise, managers at General Electric are evaluated almost in real-time through an in-house app that gathers insights from relevant organizational members at all levels, including subordinates. The survey results are then made available not only to managers and their teams but also to the superior, who will have a candid discussion with the manager if the scores are out of bounds. In addition to implementing these regular feedback systems, organizations may want to provide employees with a safe platform (e.g., a counselor, a psychologist, an ombudsman, or an anonymous reporting system) where they can report unfair treatment and have the company intervene to mitigate the negative consequences of a KUKD manager.

0 Comments