If you have ever attended a leadership seminar, listened to a CEO’s speech, or simply chatted about leadership during a coffee break, you have likely encountered an impressive amount of leadership meta-talk. Managers’ leadership meta-talk is the widespread way they talk about the positive purpose, meaning, and significance of their actions. But how often does this well-sounding talk align with actual leadership practice?

In our recent article published in the Journal of Management Studies, we explore this question by developing a theory of leadership meta-talk and the talking-doing gap—and we show why the gap between what managers say and what they do is not just common, but systemic. Potentially, but not necessarily, hypocritical. And hard to avoid.

Leadership Meta-Talk vs. Leadership Practice

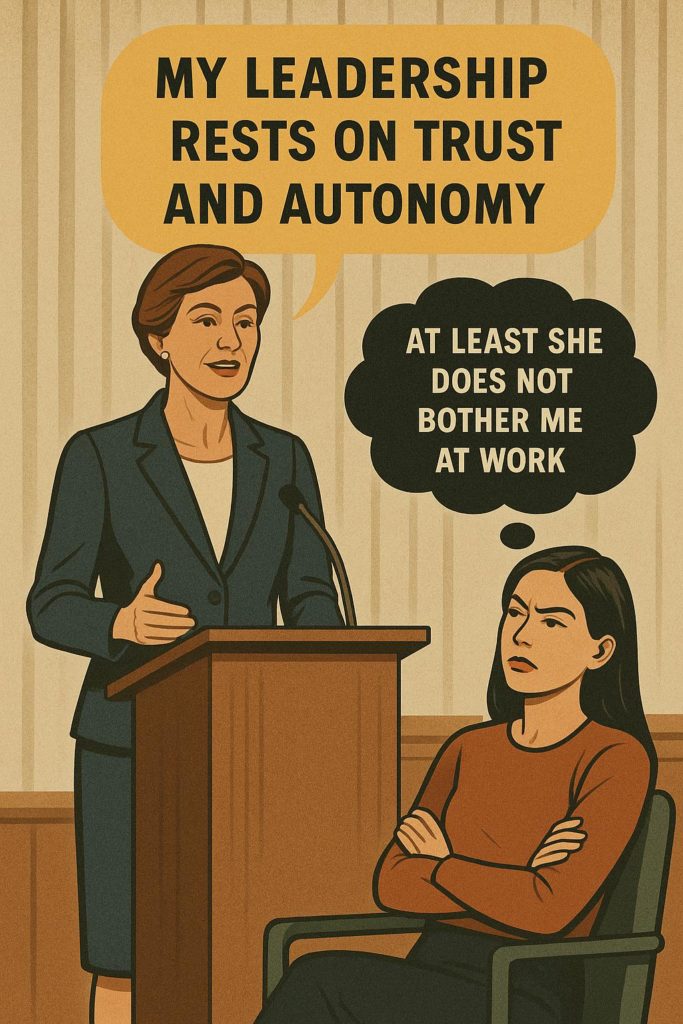

Leadership meta-talk is not simply a reflection of leadership practice. Rather, it selectively highlights positive aspects of managerial behavior and offers favorable interpretations of it. Leadership meta-talk can be aspirational when it refers to future-oriented intentions (“I want to be a supportive leader”), a form of sub-texting when it frames ongoing behavior (“I let you do this task alone because I trust you”), or an instance of sensemaking when it gives meaning to past actions (“I have always displayed a supportive style). Likewise, leadership meta-talk can be more abstract and principle-driven (“I trust my team and foster autonomy”) or more situated and casual (“I took time to listen to my team member yesterday”).

Regardless of its form, leadership meta-talk has two key functions:

- It positively influences attributions about the manager’s leadership. Stating an aspiration or self-view of being supportive can make a manager appear more supportive. Similarly, explaining one’s absence as an instance of trust can make a manager seem less disengaged and more prosocial. It portrays the workplace as more harmonious and orderly than it might actually be. A managerial self-description as supportive is an example of this. When a manager is supportive, the hierarchy appears benevolent rather than oppressive. Inequalities in status or reward also appear more justified in a benevolent setting than in an oppressive one.

This can create two types of talking-doing gaps:

- A qualitative gap, where actions are made to sound more noble or effective than they are. For example, describing one’s own leadership as supportive may only partially reflect reality. And justifying one’s absence by citing trust may gloss over muddy workplace realities.

- A quantitative gap, where occasional acts are made to appear as frequent and representative behavior. For example, although acts of supportive leadership may be rare, they might be frequently invoked in leadership meta-talk. Although such talk is not deceitful, it can still be misleading.

Why the Gap Exists—and Why It’s Not Just “Bad Leadership”

It might be tempting to dismiss leadership meta-talk as mere hypocrisy. But leadership meta-talk does not have to appear deceptively, and it can actually reduce others’ ascriptions of hypocrisy. Although leadership meta-talk portrays reality in a positive manner and has a loose and selective link with practice, this does not mean that it misrepresents reality. For instance, a manager who allows employees to complete a task independently and discusses her own absence as an example of trust may genuinely trust the employee. However, her absence may be explained by not only trust, but also less noble reasons. In addition, we argue that the talking-doing gap is largely a systemic feature of modern organizations, not simply the result of bad managers or intentional deceit.

There are several reasons for this:

- Leadership practice is hard. Truly supportive, ethical, or transformational leadership is time-consuming, emotionally taxing, and often requires prioritizing others’ interests over one’s own career advancement. For example, supporting an employee requires knowing what they need. This often requires engaging with the employee’s work or life situation, which takes time and emotional effort. It may also not align with urgent work demands.

- Leadership meta-talk is comparatively easy. Talking about values, vision, and care fits well into meetings, reports, and ceremonies—and it meets expectations from employees, peers, and top management. Put differently, talk is cheap.

- Organizational systems incentivize talk. Institutions often reward managers for articulating grand leadership visions rather than for the difficult, often invisible work of practicing everyday leadership. Performance evaluations are usually conducted by higher-level managers who have limited knowledge of their employees’ actual duties, yet pay close attention to their meta-talk.

Moreover, leadership meta-talk offers managers real benefits: it helps maintain their self-image, smooths relationships with employees, and builds a positive public persona. It also serves organizations by reducing visible workplace tensions and reinforcing the legitimacy of hierarchical structures.

Should We Be Cynical?

Not necessarily. Slightly grandiose leadership meta-talk is a normal—and even functional—part of organizational life. However, it is important to maintain a critical distance. Managers, employees, and observers alike should be aware that the glamorous language of leadership often exceeds the messy realities of leadership practice.

For managers, this awareness and critical distance can prevent painful identity struggles between who they aspire to be and what they can realistically achieve. For employees, a critical distance can protect against disillusionment and help maintain realistic expectations. For society, it offers a more grounded understanding of leadership without swinging between naive hero-worship and outright cynicism.

Final Thought

Leadership meta-talk is not inherently good or bad—it is a form of social influence. It can build hope, shared meaning, and a sense of purpose. But it can also be manipulative, mask inequality and workplace tensions, and contribute to managers and others having little understanding of what goes on and what leadership that does take place – or does not take place. Recognizing this duality is crucial. By taking leadership meta-talk seriously—but not literally—we can better navigate the realities of leadership in contemporary organizations.

0 Comments