With more and more people migrating across borders, it is very important to study the effects of migration for people and organizations. For instance, emerging economy citizens have been migrating to various parts of the world in search of economic opportunities, a process referred to as the African diaspora. The diaspora is made of migrants living across the world outside of their country of origin and contributing to societies across the world. Migrants economically enrich host societies by means of pursuing economic opportunities. Migrants not only create economic opportunities, but also culturally enrich the communities they inhabit when migrating. Such cultural exchange could be referred to as ‘total cultural capital’, a concept introduced by us recently. In our study, we raised the question of whether a more comprehensive understanding of the intricate relationships between diasporas and local communities that give rise to new cultural groups may be facilitated by a “total” approach. We use the term “total” from the sociological literature [1, 2] , which argues that a sociocultural reality is a complex combination and integration of the different elements of the social forces at work rather than a simple sum of the parts. Durkheim called this intricate integration the “collective conscience.” As a result, unlike earlier notions like the business case, which primarily focused on the economic utility of cultural capital, our concept of Total Cultural Capital takes a different perspective [3, 4]. Rather, it is based on a moral and ethical justification that promotes human integration in a society where sociocultural ties are becoming more and more interwoven. It is crucial to remember that the interplay between diasporic forces and indigenous cultural landscapes results in sustainable cultural linkages and hybrid socio-cultural settings. Naguib [1] recognized the cultural aspects of sustainability and promoted the value of traditions working together for societal progress. TCC provides fresh insights into how these results could help other communities utilizing shared physical and cultural space.

Our use of total cultural capital stems from Durkheimian sociology, which emphasizes the importance of collective conscience, which is made up of a society’s shared values, moral standards, and attitudes. The basis of overall cultural capital is the collective conscience, which is made up of the dynamic forces resulting from the convergence of different subcultures, namely those of the host and expatriate groups. Thus, a high degree of dynamic cultural integration leads to total cultural capital.

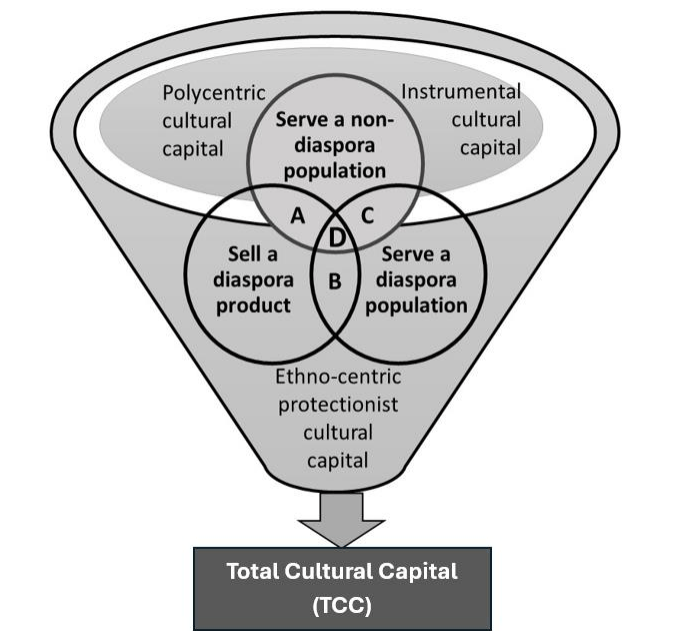

The notion of mixed embeddedness [5] appears to be the most related concept to our idea of total cultural capital. These authors view migrants immersing themselves in the local culture and espousing its creative aspects as the foundation of successful negotiation of the host cultural space. Nonetheless, such a perception may be rejected as it portrays integration as a one-directional course and has immigrants to blame if integration fails. Such a perspective does not consider the issues of race, psychological disadvantage that result from dislocation, the loss of some cultural capital, and the weight of the imperial legacy [6, 7]. Thus, our concept of total cultural capital transcends the economic rationality on which previous studies have focused. Current narratives largely perceive the economic benefits and implications of diasporas, but seldom the human dimension, such as integration, the psychological toll it takes, etc. Total cultural capital does not represent an evolutionary line but exemplifies [8] idea of organic solidarity, which encapsulates a deeper acceptance of economic and socio-cultural differences. Total cultural capital encapsulates four concurrent spheres (A, B, C, D) of integration. In Figure 1, we illustrate how these spheres work together.

Sphere A: Polycentric cultural capital—cultural diversification

This view of diaspora cultural capital involves piecemeal actions on both diaspora and non-diaspora groups. This is akin to [9] theorization of cultural capital. Polycentric cultural capital entails that a socio-economic entity is involved in some diversification, which leads them to display some diasporic products, services or cultural exhibits.

Sphere B: Instrumental cultural capital

This level of diaspora cultural capital articulation is set in the context where the diaspora population seeks to interact with non-diaspora capital. Such interactions are equally geared at displaying signs of openness and raising financial gains by increasing the customer base, thus commodifying cultural capital. As in Sphere A, there are unilateral attempts by various diaspora groups to engage with host cultural capital on a transactional basis.

Sphere C: Ethno-centric protectionist cultural capital

This trend is often more prominent in ethnic enclaves. There is a minimal attempt to embrace the host cultural capital and vice versa. The rationale is about developing their cultural capital independently of the host culture and vice versa, often resulting in tensions. Minimizing such tensions sits at the heart of our proposed concept of Total cultural capital, which is the arena of Sphere D of our conceptual framework.

Sphere D: Total cultural capital

Diaspora groups and host collectivities mix collaboratively and in a dynamic way. Diasporas are profoundly engaged with local cultures. Equally, host communities will have vested interests in diaspora capital and assist them in making such capital available to all. Sphere D groups imply that total cultural capital has three dimensions: appropriation, customization, and deployment. Appropriation: both the diaspora and the host community recognize valuable aspects of the other culture, embrace it and develop intimate affective relations with it. Customization: to effectively use these aspects, the appropriator must adapt the aspects appropriated from the other culture, thus, customize them because some aspects of that culture may not fit due to the absence of native cultural competencies and natural cultural and environmental conditions. Deployment: this concept entails cultural intelligence and competence; the actors of the multicultural domain must use the cultural elements appropriated and customized for these to become fully fledged parts of their cultural capital and embodied in daily social and economic lives. Creativity in Sphere D is further evidenced by [10] who found that there is a significant transformative strength in the interaction, appropriation and integration of different values brought by different diaspora groups. This position has significant literature backing [11] and is particularly interesting as the attempt to identify the attributes that make a host society desire a diaspora group; these attributes are not just in terms of contribution to the economy but relate to the degree of active social involvement.

Total cultural capital transcends the idea of adaptation. While structural embeddedness is understood from the perspective of the diaspora’s engagement with larger socio-cultural networks, relational embeddedness is understood by [12, 13] concerning individuals’ engagement with personal relationships. Our concept of total cultural capital transcends personal relationships and social networks to involve more dynamic exchanges (what we termed cultural appropriation). In total cultural capital, we speak of collaboration and, more profoundly, of complicities. These latter terms imply a deeper engagement between and within ethnic communities [13]. Total cultural capital is not conceptualized in terms of the formation of a cultural by-product aiming to dissipate authenticity for material gain as represented in the conception of cultural capital of Bourdieu.

In conclusion, it is important to note that the TCC can be used by policymakers or non-academic stakeholders. For example, in national immigration policy formulation, drawing on the Total Cultural Capital framework would mean that the focus on training migrants to integrate will shift to a dual approach. This signifies an understanding that both hosts and newcomers need equal amounts of training to foster integration and improved race relations. This is also true in organizations where the emphasis of diversity training has been on locals rather than migrant employees – a dual approach, particularly sitting the two groups in the same training forum will allow them to develop total cultural capital.

0 Comments