Markets focused on products and services with an explicit social or environmental added-value, such as fair trade, microfinance or organic farming, naturally seek to grow and attract new participants. Yet, doing so may jeopardize the market’s founding moral mission and alienate the support of pioneers eager to preserve the purity of such mission. Our recent paper published in the Journal of Management Studies highlights the delicate balancing through which leading organizations in such markets adapt the founding mission to pursue growth, while at the same time convincing pioneer organizations to maintain their support and avoid accusations of “mission drift”.

Balancing market growth and mission fidelity

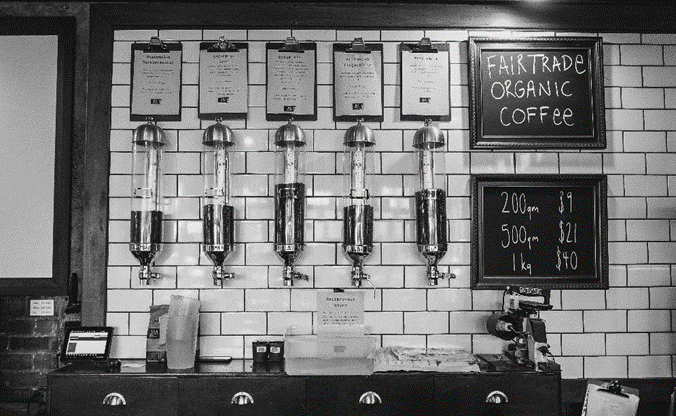

What do fair trade, ethical investment, locally sourced food, microfinance or citizen-based renewable energy have in common? These “moral markets” have all been created with the mission to offer a morally superior alternative to “conventional” markets. For example, pioneer fair trade organizations were created to offer better prices and more equitable trading relationships to small-scale producers in developing countries, while also lobbying governments and industries to bring more justice in international trade. Driven by the willingness to gain visibility and scale the achievement of the moral mission, moral market organizers tend to pursue market growth by developing certification standards and attracting new participants, including large businesses not necessarily sharing the same commitment towards the founding moral mission. As a consequence, market growth may lower the barriers to entry at the expense of preserving the founding moral mission, which may attract critiques from pioneer organizations and threaten the moral legitimacy of the market. Indeed, if consumers and activists perceive the moral added-value has been watered down, they may withdraw their support and cause moral market collapse. How market organizers such as certification organizations avoid this outcome while pursuing market growth is a challenge that we explore in our paper, using the emblematic case of fair trade.

The puzzle of fair trade market growth

Our study finds that since the launch of fair trade certification in the late 1980s and its international integration through “Fairtrade International” in 1997, numerous changes have been brought to the initial certification standards. These changes aim to facilitate the participation of large businesses and multinational corporations. For example, plantations can now be fair trade certified in which producers are salaried workers, instead of working only with producer-owned organizations as initially foreseen; and products can now be certified even with only one fairly trade certified ingredient, instead of requiring all ingredients to comply with fair trade standards. These changes could have caused huge protests by pioneer fair trade organizations, leading to a massive loss of support from consumers and activists. However, we found that critiques have been very discrete and mainly remained internal to the fair trade movement. How can we explain this surprising observation?

Downplaying, justifying and stabilizing change

Our research reveals three avenues through which a moral market organizer, for example a certification organization, can scale the market while avoiding accusations of “mission drift” and maintaining a collaborative relationship with pioneer organizations. First, the mission can be simplified to focus mainly on the dimension that is most compatible with market growth. In our case, Fairtrade International foregrounded a quantitative interpretation of the initial mission, focused on raising revenues for producers, and side-lined the initial political mission of advocating for international trade justice. By doing so, Fairtrade International could downplay the extent of the changes and emphasize continuity with (part of) the founding mission. Second, mission change to enable market growth can be justified as morally consistent with a set of moral claims. In our case study, we identified how personal claims used at founding (based on the personal relationships with small-scale producers) were increasingly complemented with procedural, impact and governance-related claims in order to bring broader moral justification to growth-oriented mission change. Third, the moral market organizer can leverage the common fate uniting all market participants, including pioneer organizations, so that their common interests are emphasized over their differences. These common interests may take the form of “red lines” that represent non-negotiable moral thresholds. In our case study, we witnessed how Fairtrade International invested in collaborations with pioneer organizations after each mission change episode and convinced them that the market remained focused on the mission of improving the livelihoods of small-scale producers.

Towards temporary truces

While mission change may be initially resisted by pioneer organizations, it is possible for moral market organizers to regain their support through downplaying, justifying and stabilizing mission change. Such actions do not suppress disagreements within the moral market but they enable participants to reach “temporary truces” around the core mission, ensuring the maintenance of moral legitimacy in the market. Our findings are applicable to moral markets that seek to grow without compromising their moral legitimacy, in particular those with one central market organizer. Future studies could explore whether and how such temporary truces may be achieved when there are multiple market organizers (such as competing certification schemes), or when the founding mission is less amenable to quantifiable standards.

0 Comments