Gro Kvåle and Zuzana Murdoch

The company we keep is often perceived to say a lot about who we are and what we stand for. Whenever we voluntarily interact with a certain person or organization, this can be interpreted by those around us as a tacit expression of agreement with, or even support for, their actions, views and standpoints. Hence, it is common to be judged not only based on one’s own decisions and actions, but also based on the attitudes, values and ethics of family, friends, colleagues or even business partners. As a direct consequence, our interactions with those carrying a deeply discredited or flawed identity in the eyes of a large segment of society might involve a serious risk of contamination. Come too close, and their negative standing in society (or ‘stigma’) may well leave its stain on you.

Since such ‘stigma transfer’ can have major implications for how other people treat you – or stop treating you – a critical question is: When and how does engagement with individuals or organizations that carry a stigma lead to contamination, and what determines one’s susceptibility to such spillover effects? Answering this question is important not only to gain a deeper understanding of the nature, conditions and implications of spillovers in social evaluations. From a more practical perspective, it is also imperative to develop organizational interventions and/or managerial tactics aimed at either minimizing spillovers (among targets) or maximizing their success (among instigators). Only once we know when and why something happens can we set about devising strategies to try to make sure it does (not) happen to us again.

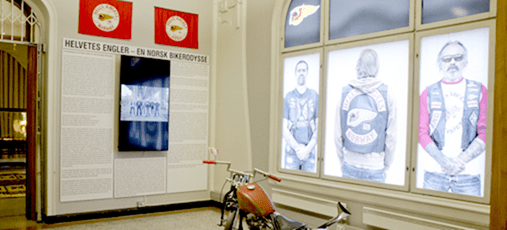

An inductive case study of art exhibitions featuring Hells Angels

To help answer this question, we study two Norwegian art exhibitions: i.e. the April 2013 Nordic Light International Festival of Photography in Kristiansund, and the May 2014 exhibition “For the Love of Freedom” at the University of Oslo’s Museum of Cultural History. Both exhibitions involved Hells Angels Motorcycle Club Norway indirectly – through exhibited photographs of its members – as well as directly – through the scheduled participation of the club in public debates. The inclusion of Hells Angels in both exhibitions was highly controversial, and placed the organizers in the eye of a public storm. The main organizers of both events were highly criticised in both the private and professional sphere for their choice to include Hells Angels, and faced severe pressure from politicians, the police and the media to cancel all events directly involving club members. Our empirical analysis of the vigorous societal debates surrounding these exhibitions relies on extensive data collected from media reports, public discussion fora, official documents and interviews with key protagonists.

Shame on you!

Our main findings indicate that stigma transfer works through a multi-stage process where the emotion of shame and the activity of shaming play a central role. We show that contact with a tainted actor is often perceived to signal a lack of judgment and/or disregard of established norms. Since such transgression cannot be left without consequences (or punishment), these negative assessments set the stage for the use of purposeful shaming behaviours to condemn and denounce the involved actors. We identify such shaming both at the individual and organizational levels. The former focuses on threats of social as well as professional exclusion or marginalization – such as personal attacks on social media or active obstruction of the main organizers in the execution of their duties. The latter instead involved threats of financial retribution – including, for instance, calls for a boycott or organizations pulling out of sponsorship agreements.

Overall, we uncover considerable evidence that the activity of shaming is a way to (try to) exercize power during social evaluation processes. Shaming behaviours not only aim to re-impose established community norms, but also intend to leave a stain on the targeted social actors. While advancing our understaning about why negative evaluations may spill over from one social actor to another, this finding naturally also raises important questions about when and how best to respond. What can/should the target of such shaming behaviours do to avoid spillover of negative social evaluations? Should one contest shaming attempts, and, if so, how?

The importance of fit and status when contesting shaming attempts

The targets of shaming often actively contest these efforts by bringing forward verbal as well as non-verbal accounts in their defence. We show that it is important thereby to maintain a close fit between the image-threatening claims presented by the shamers, and the impression management strategies employed by the shamed to defend themselves. For instance, if you are being shamed for setting up a public debate with a tainted actor as part of an art exhibition, it is more useful to offer counterclaims about the importance of open debate and freedom of expression, than counterclaims emphasizing the generic value of artistic freedom. A close fit between the nature of the perceived transgression and the content of a response increases the authenticity and effectiveness of the defence strategy.

Furthermore, we find that contestation of shaming attempts has different impact depending on social actors’ current reputation or status in society. Counterintuitively, contestation by high-status actors can at times work as a further validation of their own social standing. As such, we go beyond previous research findings showing that high status actors can deviate unpunished from social norms. In fact, by defending themselves, they may well be able to reinforce their position in society. From a practical perspective, this implies that one should carefully consider shaming attacks on high-status actors as these can sometimes backfire.

The emotional aspect of shaming tactics

Overall, voluntary engagement with tainted actors prompts shaming attempts, which, if not deflected via counterclaims, can trigger a stigma spillower effect. Such ‘shaming tactics’ imply that emotions are often at the heart of social negotiations. It is therefore critical to understand their role and importance in your relations to the outside world. Keeping a close eye on emotions is vital to increase your ability to manage the emotional climate.

Read the full study published in the Journal of Management Studies here.

Keywords: Courtesy stigma; Episodic shaming; Social evaluation; Status; Stigma-by-association.

Photo: Museum of Cultural History, UiO / Toril Cecilie Skaaraas Hofseth

0 Comments